For the purposes of this article, the following theoretical epochs will be identified, described and applied to Bitcoin adoption, resistance and narratives: classical theory, neo-classical theory, systems theory, human relations theory, power and politics, chaos theory, critical theory, inter-governmental relations and interpretive theory. Bitcoin will be addressed as an asset class which spans all the theoretical models presented and one in which alternative asset classes are being demonetized.

Part One: A Quick History Of Thinkers

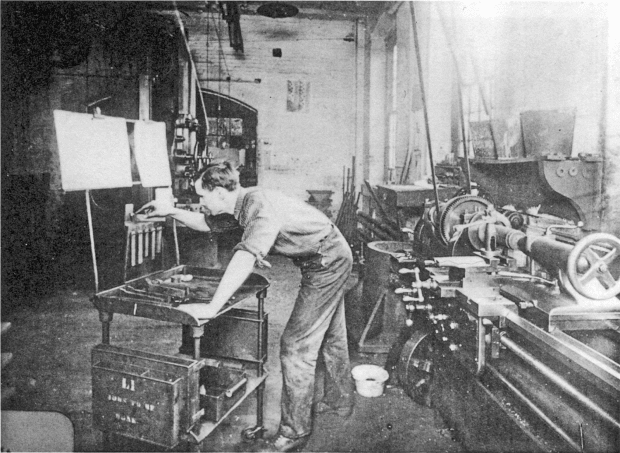

Classical theory crash course: In 1911, Frederick Taylor published the “Principles Of Scientific Management,” where, in essence, he proposed that there was one best way in order to do, essentially, all things. The theory was integrated into a variety of real-world applications, most notably, the production of the automobile. As such, Taylor’s model revolutionized the assembly of vehicles by reducing the worker to a single task in many cases. Assembly lines grew in popularity, production costs decreased, profit margins increased and humans got carpal tunnel syndrome from having to insert the same bolt, on the same part, for the same car, for a lifetime. This was, for all intents and purposes, classical theory at its finest.

Classical theory posits that organizations exist to accomplish an economic goal.

A machinist at the Tabor Company, a firm where Frederick Taylor’s consultancy was applied to practice; image from approximately 1905. Source.

Neo-classical theory crash course: “Neo” is just a fancy word for new, however, when coupled with “classical” (old), it is an oxymoronic phrase, i.e., the “new-old” theory.

A few decades after Taylor’s theories became reality, Herbert Simon was publishing work and introducing coined terms such as “saticficing” (a hybrid of the words “satisfy” and “suffice”) to explain administrative behavior when presented with difficult decisions, limited information, knowledge, resources or worse, according to “Classics Of Organization Theory.”

There were thinkers far ahead of their time during the neo-classical era, such as Mary Parker Follett, a classical thinker who raged against classical thought. In her mind, Follett believed that employees were reduced to being “cogs in a wheel.” Follett proposed that people were not a unit of operation, as noted in “Classics Of Organization Theory.” She cracked the door open for subsequent theories, such as systems theory and human relations theory. As neo-classical theory’s sun had set, the era was defined not by forward thinkers such as Follett, but rather by organizations being seen as self-contained islands which could be finely tuned for maximum efficiency and that humans were analyzers and decision makers for these islands.

Systems theory crash course: Herbert Simon blurred the line between neo-classical and systems theories, as his impact spanned both epochs. Within this era, each part of the organization could only be understood in relation to the other parts of the system; this was later translated to “survival” of the system. Katz and Kahn (1966) introduced the world to the notion that the independent and isolated islands (organizations, business, etc.) were not so isolated after all; these systems required energetic inputs and outputs (think raw materials, parts, ideas) and once introduced, they would “energize” or “re-energize” the system. As a result, systems theory opened the door to the idea that organizational systems, while complex systems within themselves, were also part of a greater, external system, per “Classics Of Organization Theory.”

Human relations theory crash course: Human relations is also known as human development, human resources, human capital, etc. During this era, thinkers such as Abraham Maslow (“Hierarchy Of Needs”) and Douglas McGregor (Theory X and Theory Y) took center stage; and the “motivation theory” era was born. While the “hierarchy” has been adapted over the years to include upper tiers of “transcendence,” Maslow’s original proposition, that human “needs” had to be met in order for people to not only survive, but thrive in organizations and in life, took off like a wildfire. The visual below represents a simplified model where each person starts at the bottom and attempts to work their way up.

McGregor took the motivation components of Maslow’s work and adapted them to a concept of management. McGregor introduced Theory X and Theory Y. Simply put, people who view the world through a “Theory X” mindset view humans as unmotivated. Theory X proposes that humans avoid responsibility, have little ambition, are lazy and as such, rewards and punishments are required by managers.

If you’re nodding your head, you probably view the world through a Theory X mindset, or had a supervisor who did, and as such, if you’re a manager or supervisor, you probably micromanage your employees; and if you were micromanaged, you might have had a supervisor who saw you as lazy, unmotivated or lacking ambition. This is also where the phrase “carrots and sticks” took off in the management world.

Theory Y is different. A Theory Y mindset proposes that humans are intrinsically motivated and as such, given that the human is doing something fulfilling, the work itself is the reward; no carrots or sticks needed. One could argue that the fictional character Ted Lasso essentially views the world through a Theory Y filter. Human relations theory presented to the world that individuals have an important role in an organization. The idea of suggesting that you might have the right people but that they could also be in the wrong spot took root.

Power and politics theory crash course: This theoretical era should really be entitled “power, politics and influence” but we can’t go back in time and re-coin it, so here we are. John French and Bertram Raven identified five forms of power, however, the underlying framework of the theory really questioned the difference between power and leadership. I’m sure there is an arsenal of examples that will flood your mind once they are listed in a moment; please know that it’s ok to pause and reflect (cringe) as you recall terrible (traumatic) leadership of your past, but when you snap out of it, let’s continue.

Reward, expert, referent, legitimate and coercive power were foundational concepts for this theoretical era. This is also the era where theorists such as Karl Marx attempted to describe what they perceived as exploitations of the middle class through the “exploiters” (bourgeoisie) and the oppressed (proletariat).

Chaos theory crash course: If you have been involved in a restructuring, reduction in force or “right sizing,” you can empathize with the disequilibrium created as one system breaks, experimentation commences and a new system is formulated or reformulated. Kurt Lewin acknowledged this when he reminded the academic community that profound change occurs when a whole system changes. Chris Argyris introduced concepts such as double loop learning and models such as the ladder of inference.

In chaos theory, there was a significant focus on the process being more important than the structure, as outlined by Cornell University Professor Steven Strogatz in “Nonlinear Dynamics And Chaos.”

Critical theory crash course: In the more recent era, Jürgen Habermas proposed that language shaped life, per “Classics Of Organizational Theory.” As such, reasoning models and the use of verbiage could (would and had) shaped the world. Robert Denhardt proposed that citizens distrusted bureaucrats and as such, distrusted government

Critical theory opened the door for quotes such as, “We know they are lying, they know they are lying, they know we know they are lying, we know they know we know they are lying, but they are still lying,” attributed to Elena Gorokhova. Critical theory proposed that humans were in conflict with “the self” and that a voice should be given to those who cannot be heard.

Inter-governmental relations (IGR) theory crash course: IGR was the era of Roosevelt and Reagan as well as policies such as The New Deal, social security and welfare, according to Victor Pestoff; as well as counter measures such as a reduction of national grants to states and an attempt to separate states from the federal government. In the most simple sense, IGR works to explain the relationship between different “governments” within one country. Within the U.S. for example, there are a variety of “governments” which exist and work, some harmoniously, some, well, not so much, as Pestoff explained.

Interpretive theory crash course: Congratulations, you’ve reached the end of the abbreviated crash course; know that each of these sections have many more theorists, researchers and material to cover if you’re interested. Interpretive theory can be a bit of a mind bend, and with limited characters, I’ll do my best to keep it simple. Get your head ready for perceiving the world through “The Matrix.”

There are three theorists we can focus on to help clarify the confusion. Emmanuel Kant, Alfred Schultz and Peter Berger; again, there are many more, but we’ve got to stay on track. Kant proposed that the ultimate reality was held within the spirit or an idea more than what was perceived to be that idea; as such conversations of morality grew, as is explained in “The Social Construct Of Reality” and “Classics Of Organizational Theory.”

Schultz saw the world through a lens of understood meanings, which were subjective, per “Classics Of Organizational Theory.” For example, two people could witness the same event and come to different “realities” of what had occurred based on their perspective, experiences and biases. Finally, Berger worked to describe the social construction of reality. Avid readers who have explored Miguel de Cervantes’ work, “Don Quixote,” will grasp this concept quickly. A potentially value-free society (social science) gained traction during this era.

These theoretical models, from my perspective, will play a role in how Bitcoin and Web 3.0 will be understood for generations to come; not only in an academic sense, but in what society perceives to be their reality.

Part Two: Dear Bitcoin, Welcome To The Theoretical Model Universe

One could make the argument that at every epoch presented above, Bitcoin was bound to have taken root. From a classical model and a “one best way” solution to the money problem, future theorists may propose that Bitcoin is the most rational economic principle and as such, the set structural arrangements and behaviors coded into the software and algorithms accomplish the economic goals of the world. Bitcoin as perfect money addresses the need for an alternative financial system in the future.

Neo-classical theorists could suggest that Bitcoin “satisficed” its way through the early years. Soft and hard forks, the Lighting Network, Taproot, etc., are examples of the Bitcoin ecosystem coming to the realization that it is no longer a self-contained island and that the Bitcoin system exists within a system of systems, some which help and some which attempt to compromise the protocol. I perceive this as those kids who discovered a no-name band long ago and, once the band became popular, songs were interpreted in alternative ways that what the original followers believed. The new interpretations frustrated early adopters and in the end, growth occurred regardless of the original adopter’s perceptions and intentions.

Systems theorists might posit that Bitcoin’s adaptations were integral to the survival and adoption of the protocol on a global scale. Theory X thinkers might view Bitcoin as a solution to distrust, while Y theorists may provide a counter-thesis and suggest that Bitcoin represents value from the truest and purest of forms.

Human relations theorists may propose that individuals involved with the development and continued support of the protocol represent real people, who, in turn, house the most significant aspect of the system; survival. Eventually servers will need repair or upgrade, integration software and hardware will evolve and experiences will be shared; all coordinated by humans.

Power will be garnered in a variety of ways, through legitimate means, referent belief, reward incentives, coercive tactics or expertise via commentary. Class systems may change, some in power once may lose their soap boxes or swords and others who had no influence may gain leverage. Learning will occur and those who apply a reflexive or double-loop approach may have a competitive advantage.

Critical theorists may propose that Bitcoin’s birth was from an inherent distrust of government. Perhaps that, when the history of Bitcoin is written from a theoretical perspective, they’ll argue that it all began with theorists such as Denhardt.

IGR theorists might argue that true Bitcoin adoption (or failure) lay within how governments, at all levels, adopted or shunned the technology. How bureaucrats had to have conversations about the technology and how the potential adoption or rejection would alter local municipalities, counties, states and the country forever.

Finally, interpretive theorists might bring into focus the difficulty some have in defining what is reality; as such, one hurdle for early adopters and skeptics to overcome is rooted in a deeper question of their own perceived reality.

In some respects, all perspectives detailed above would be correct. In others, they are all deeply flawed when examined individually. Greater thinkers than myself will flesh out where Bitcoin “fits” into the theoretical models and in history well into the future.

Part Three: Bitcoin Engulfing History, Assets And Theoretical Modeling

A NASA engineer once tried to explain blackholes to me, from my perspective it was similar to my failed attempts at explaining Bitcoin to a great-grandparent. One aspect of the black hole conversation, however, stuck with me: the idea that the gravitational pull of a black hole is so powerful that even light cannot escape it. That concept was profound to me; somewhat painful and horrifying, if I’m being honest.

Once that concept settled and I came to grips with it, I had questions flooding my consciousness. Getting orange pilled or wrapping one’s head around Bitcoin is a similar experience for some, I propose. When skeptics zoom out from the day-to-day price fluctuations and look longer term, even with 80% or more price swings, there has been no better place to store your wealth in the last decade.

This is a profound concept, but again, we are early. Plumbing, electricity, automobiles and the internet were all fads at one time. Without Keynesian economists there to provide a flood of currency or a stock exchange deciding to “halt trading” when an asset “moons,” there will be massive moves in both directions as the market determines the value; this is how an asset should act in a free economy during price discovery.

There have been countless articles, opinions, videos and peer-reviewed papers that describe how Bitcoin is currently “eating” other asset classes; a theoretical black hole of the investment world. A simple example of what could be engulfed would be the bond markets. Yet, the real estate market, as one thinks a bit beyond what is right in front of them, is where the universe could begin to fall into a proverbial Bitcoin black hole death spiral.

In the simplest sense, consider an investment property in a desirable location; something that could be purchased, renovated and listed for rent. This property, for the owner, might have an ultimate (potential) goal of being an inflation-adjusted revenue stream for the owner for years to come. A property like the one described would then attract not only local investors, but national and international investors.

As one looks onto the horizon, if bitcoin becomes the store of value some predict it could be, some investors may question if taking on the risk with a property is worth it. Could an investor not simply store their value in bitcoin and as such, would bitcoin not have just “eaten” a piece of that real estate market? Cue the black hole reference. This is what folks mean when they say Bitcoin is “demonetizing” other assets. I propose Bitcoin is also “dematerializing” more than just financial institutions as well; it’s just a matter of time.

Would home prices not stabilize and become more affordable for residents who actually wanted (needed) to live in a home that wasn’t on an investor’s radar? What about gold, silver or other commodities? Wouldn’t, couldn’t or shouldn’t stability come after speculators have been drawn to another asset?

Yes, “shouldn’t” is a loaded word. I walked into the office of a mentor once, who happened to also be a pastor. I had excuse after excuse of why I should have done this and I shouldn’t have done that; in truth, I was a bit of an idiot years ago, less so now, but not by much. He stopped me in my tracks and said, “Son, you’re ‘shoulding’ all over yourself; thou shalt not should. Do it, or don’t do it, but shut up about it already.”

So, I agree, history will play out and we will have commentary from every angle about how something “should have” or “should not have” occurred, but in the end, it will have occurred or not occured; but Bitcoin will still be there. The protocol will outlive us all.

Bitcoin will not theoretically engulf or demonetize gold, silver, bonds, real estate and a variety of other investment avenues; bitcoin is demonetizing parts of these asset classes, now. The same can be said in regard to typical “savings” accounts at traditional banks.

Sure, traditional thinkers and folks who might even hate Bitcoin, the entire crypto space or truly despise the newly-minted crypto millionaires and billionaires, might be hard pressed to rationalize .01% versus 9.0% interest or more on stablecoins. With debit cards becoming available that directly link to stablecoins, why does anyone need a debit card from a traditional bank? Third-party applications have already built apps that allow customers to use bitcoin as collateral to finance purchases. Let the engulfing commence.

One aspect that the academic community may wrestle with in the future might be where to categorize Bitcoin in regard to its origins. In a macro view of history, this may be trivial, but academics base their careers on “coining terms,” and YouTubers base their reputations on “calling tops;” there is a decent amount of human capital at stake with this trivial endeavor.

Yes, the 2008 financial crisis was the potential straw that broke the camel’s back, but is the origin of Bitcoin both more and less complex than this single event at the same time? Let’s see if we can “label” Bitcoin according to those theoretical models detailed above by asking some questions.

Does Bitcoin, in some respects, fall into a “one best way” model of Taylor’s “Scientific Management” and classical theory? Has the crypto community begun to realize that Bitcoin is not a standalone island, and as the space matures, do we not begin to see how some applications “satisficed” and iterating into maturity? Can anyone separate the conversation of Bitcoin from trust and distrust? Bitcoin must fall into the classical or neo-classical arenas then, right?

Are McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y models more relevant today than they ever have been before? What about Maslow’s “Hierarchy Of Needs”? Bitcoin articles have already been published correlating Maslow’s work. Has Bitcoin become a vessel in which all layers of the model, from physiological needs to self-actualization, include Bitcoin? If that is the case, Bitcoin should rest in HR theory, one could argue.

What about politicians and bureaucrats? Are we only a few years out from power and politics theory becoming center stage? Are we not already in the midst of a conversation of the exploiters and the oppressed? Doesn’t Bitcoin attempt to solve this issue? How about rewards, coercion, legitimacy, referent or expertise in the crypto community? Who has gained traction as an intellectual thought leader in the Bitcoin space? It seems as if Bitcoin has taken over power and politics as well.

Have communities not already been thrown into disequilibrium; are current financial bedrocks now on unstable ground? Isn’t Bitcoin currently in the “experimentation” phase of chaos theory? Have protocols not already iterated, have double-loop learning models not already been (and continue to be) applied as developers adapt and innovate? Wasn’t the original idea of Bitcoin begun with a distrust of the government? Chaos theorists are nodding their heads in amusement.

Critical theory is in play as well, giving a voice to those unheard, or unbanked in this scenario; this is a goal, is it not? Haven’t governmental relationships already taken root in some arenas, or been cast out in others? And hasn’t the concept of “real” versus “virtual” assets already split the globe as the world grasps with what is reality and perception when considering bitcoin as a viable inflationary hedge? So, which is it?

I would propose that Bitcoin has roots in all of the theoretical models simultaneously; as such, Bitcoin as a whole, has origins in all and none at the same time. Bitcoin is a black hole when explored through the lens of demonetizing alternative asset classes, but Bitcoin is also a black hole of theoretical models and everything in its path. Bitcoin alone solves problems humans haven’t even considered yet.

I propose that Bitcoin will pull into the vortex all academic fields of study; from psychology to business, and criminal justice to public administration. All academics will have their once stable and tenured footings, loosened by a changing landscape, one that includes Bitcoin in some manner. If academic communities are not discussing Bitcoin, they should be.

Colleagues of mine see the organizational theoretical models (classical, neo-classical, systems, HR, power and politics, chaos, critical, IGR and interpretive) chronologically, like chapters in a book or a timeline. I too was trained this way. For generations, this was an accepted and appropriate construction of reality. Bitcoin has bent this reality. What came first or second on a linear theoretical continuum, now occurs simultaneously, violently and chaotically, while maintaining uniformity, patterns of behavior and rationality.

The reality is both physical and virtual; real and imaginary. As the world becomes not only aware of the space, but chooses to embrace or refute it, it is only a matter of time before theoretical modeling falls into the growing black hole of what Bitcoin’s reach consumes.

Bitcoin is a space that can be both rational and irrational depending on one’s perspective; exciting and boring; innovative and traditional; as well as uniform and disorganized, concurrently.

When asked if classical theory can be applied to Bitcoin, the answer is yes and no. Neo-classical theory, the same; systems theory, ditto; and so on. The black hole of Bitcoin has gone beyond demonetizing assets; the space has developed a reality in which opposing realities, perspectives and even a disbelief in the entire existence of the space, can coexist. It is only a matter of time before widespread conversations of Bitcoin infiltrate nearly every aspect of academia, theoretical models included.

Additional References

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1991). “The Social Construction Of Reality.” Penguin Books.

- Denhardt, R. & Catlaw, T. (2015). “Theories Of Public Organization.” Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

- Harmon, M. & Mayer, R. (1986). “Organization Theory For Public Administration.” Boston: Little, Brown.

- Lewin, K., Heider, F., and Heider, G. M. (1966). “Principles Of Topological Psychology.” New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co.

- Marx, K. (1996). “Das Kapital” (F. Engels, Ed.). Regnery Publishing.

- Maslow, A. and Frager, R. (1987). “Motivation And Personality.” New York: Harper and Row.

- McGregor, D. (1960). “The Human Side Of Enterprise.” New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Pestoff, V. (2018). “Co-Production And Public Service Management: Citizenship, Governance And Public Service Management.” New York, NY: Routledge.

- (PDF) “The Bases Of Social Power.” ResearchGate. (n.d.). Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- (PDF) “Scientific Management Theory And The Ford Motor Company.” (n.d.). Retrieved January 8, 2022, from Shafritz., Shafritz, J., Ott, J. & Jang, Y. (2016). “Classics Of Organization Theory.” Australia Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Strogatz, S. (2015). “Nonlinear Dynamics And Chaos: With Applications To Physics, Biology, Chemistry, And Engineering.” Boulder, CO: Westview Press, a member of the Perseus Books Group.

- Taylor, F. (1998). “The Principles Of Scientific Management.” Mineola, N.Y: Dover Publications.

This is a guest post by Dr. Riste Simnjanovski. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.