For full context, make sure you read Part One of this two-part series before continuing. In it, we discussed how the United States’ irresponsible spending stems from the fiat money system, which allows them to engage in continual abstract wars (such as “the war on drugs”) and how a return to a sound monetary standard through bitcoin would stop the endless conflict we’ve experienced over the last century.

War On Poverty

The War on Poverty — the granddaddy of the United States’ poor spending habits.

58 years ago, former President Lyndon B. Johnson launched a war which would eat into people’s wealth all while trying to cure wealth inequality — a contradiction for the ages.

Nevertheless, good intentions birthed this series of legislative actions. At the time, more than 20% of Americans were considered poor and Johnson was convinced that state intervention was the most viable way to bring the country back to its feet. While it was supposed to be “a hand up, not a handout,” Johnson’s legislation couldn’t be further from that ideal.

Over $800 million has been spent to eliminate poverty since his series of initiatives came to pass.

What do we have to show for it? Welfare rolls have expanded, as the horrifying truth of government dependence has come to fruition for many. The notion of equal opportunity is phenomenal, but rather than cutting red tape and encouraging job creation, wealth was taken from those with more and given to those with less. Some of those on the program leveraged the government assistance to build a life for themselves but given the increase in welfare dependency over the last half cntury, more people have structured their lives around the system instead of using it as it was intended, as a “hand up.”

It’s safe to conclude that the “handouts” which Johnson was so adamant about excluding have become the hallmark of modern welfare programs. The War on Poverty is a stain on the American track record of raising those with nothing to prosperity – providing equal opportunity for all who reside “from sea to shining sea” to work or to innovate their way to prosperity.

Funding for such programs would have to become almost entirely voluntary under a bitcoin standard, as taxes could never be high enough to replace the U.S.’s decades-long penchant for money printing. Any functional and accepted state program would be funded by those philanthropists who want to contribute to the cause, and due to this limited available funding, decision-making would be more precise by necessity. When scarcity is a factor in any decision, capital allocation is naturally done in such a way that leads to the optimum outcome. Under fiat, money can be created and seized at any given moment, so the concept of scarcity never plays a hand in decisions — hence why government programs often resemble inefficient money vacuums more than they do functional value-adds.

While the War on Poverty was the first case study in the inefficiency of government capital allocation, it wouldn’t be the last. Once they discovered their universal solution, the money printer, the necessity for sound money would become even more apparent to the American people.

War On Drugs

The string of government initiatives beginning in the 1970s to end drug usage was the second of four periods of “war on the abstract” that the U.S. has engaged in over the last century.

Starting as far back as 1914, the regulation of opiates and cocaine began passing in the halls of Congress, followed by Prohibition, followed by the introduction of a heavy marijuana tax in 1937, as well as imprisonment and fines for possession. This was just the beginning of something far more concerted and targeted in the United States — the war on drugs.

In 1970, the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was signed into law by President Richard Nixon, introducing an arbitrary “schedule” to classify drugs and ascribe criminal punishment to them. And in June of the following year, Nixon declared a war on drugs, citing drugs as “public enemy number one.”

Ironically enough, Nixon suspended the convertibility of dollars to gold in August just two months later; his money-sucking initiative was followed by the nail in the coffin for the dollar as a sound representation of gold. Ultimately, this was necessary: To pursue these lofty public initiatives while continuing to finance the war in Vietnam, something had to give.

Was the United States going to levy a higher tax burden on its citizens? No. As we discussed earlier, this would be a death sentence for any sitting president. The easy solution would be to quietly disconnect the currency from the value it was supposed to represent, despite meaning that this made the dollar a promissory note which promised nothing.

That is how you finance government expenditure, they learned. And boy, oh boy, did it feel good.

In 1973, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was created, still receiving an annual budget of $2.03 billion in 2022. The 1980s saw then-President Ronald Reagan introduce many “Just Say No To Drugs” campaigns – such as the elementary-school-targeted D.A.R.E. programs? The crackdown on even the phrase “drugs” was now underway.

The cost of this endeavor has been an estimated $1 trillion as of 2015. That’s a hefty tag to pay for an arguably failed attempt at eradicating drugs from the American paradigm (remember this theme for later). Fiscal irresponsibility was sparked by the legally-recognized ability to magically create dollars out of thin air. And this was just the beginning.

War On Terrorism

Now we arrive at the main subject matter of this article, the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) much more popularly known as “the war on terror,” a term coined by then-President George W. Bush. It was meant to be a catch-all term for war against all terrorist groups (not just Al-Qaeda who claimed responsibility for the 9/11 attacks) which should have been the first signal that perhaps the United States was biting off more than it could reasonably chew.

Al-Qaeda was allowed to operate with impunity under the protection of the Taliban regime, so the idea was simple: move into Afghanistan to destroy Al-Qaeda, kill Osama bin Laden and remove the Taliban from power. However, the war on terror in the Middle East did not stop here.

Bin Laden fled to Pakistan, and in 2003 the United States invaded Iraq, with George W. Bush infamously claiming that we needed to remove a regime of terrorists which (allegedly) held weapons of mass destruction. After capturing Saddam Hussein in 2003, and executing him in 2006, the war persisted in Iraq for another four years.

The United States reportedly killed Osama bin Laden on May 2, 2011, but the war in Afghanistan wouldn’t wrap up in its entirety for nearly another decade. The full withdrawal of U.S. troops was meant to have been completed by 2014, but in 2014 it was announced that over 10,000 troops would remain in Afghanistan. To many this was an indication that this “war on terror,” like the “wars” on poverty and drugs which preceded it, would have no logical and definitive end. For now, President Joe Biden has removed American troops from Afghanistan, but he still “didn’t end the ‘forever war.’”

Like our first two wars on the abstract and indefinable, the Global War on Terrorism brought with it an ambiguous and subject-to-change price tag. The powers that be hold the baton for the entire race, so they decide when and where money is spent. Under a bitcoin standard, decision-making is forcibly prudent — you wouldn’t throw money at missions and objectives that do not provide real value, as it would be wasteful. But enabled by the reckless spending of fiat money, the war on terror incurred a heavy price: Over 7,000 U.S. service members were killed in action during post-9/11 war operations, not to mention the tragedy of well over four times that number of soldiers who have committed suicide in that same time period.

Their lives weren’t the only price to pay for the American people. For the post-9/11 wars, the total U.S. budgetary costs and obligations totalled more than $6.4 trillion through 2020. That’s trillion (with a “t”) representing over 20% of our current national debt. What do we have to show for it? While we’ve left our mark by executing some of the worlds most reviled terrorists, the people of Afghanistan are still subjugated by the Taliban, who have regained control of Afghanistan as of 2021.

Perhaps within a system that holds the spenders’ feet to the fire, our actions would have been swifter and more decisive. Maybe if the money was scarce and it came directly from the citizens through explicit taxes, we would have tactically moved in to execute those who wronged us on 9/11.

Instead of learning our lesson of avoiding any war with an unclear goal, as we should have from Vietnam, the United States continued our abuse of the money printer by going to war for nearly two more decades with an unclear end goal. But unnaccountable control of the money supply means control of the firepower.

The war on terror was a lengthy, costly, and tiresome endeavor. It was a failed attempt at eradicating a concept so decentralized and hostile that the chances of success at the outset were slim to none. And after twenty years, thousands of American soldiers dead, and nearly $7 trillion in spending, the grand finale was a hasty retreat from Kabul, leaving hundreds of Americans stranded after the embassy was abandoned. The Taliban now run Afghanistan; for all those dollars printed and all that bloodshed, we’re back at square one. The only measurable outcomes (and they’re not good ones) were the lives lost, and the trillions of dollars added to the balance sheet of the United States government — a debt burden that has yet to be, and likely will never be, serviced.

The honest and good-natured spirit of defeating those who stole our dignity on September 11, 2001, has completely dissipated two decades into the conflict. That fire from the American people has been replaced by a generation of adults who haven’t been alive in a time where the United States hasn’t been involved in the Middle East. These adults have grown to see the massive and ever-expanding debt bubble as a necessity, just a normal part of life – when this same debt bubble is what’s pricing them out of a job, pricing them out of purchasing a house, and pricing them out of raising a family. This is not normal.

The United States made a triumphant effort to end terrorism globally and came up short. But just 19 years after 2001, they’d ask us once again to suspend our disbelief, and put our money and decision-making ability into their hands. We were going to war, again.

War On Health

What do you do when there’s no war to be had? Health crisis, enter stage left.

This article is not going to argue the origins of COVID-19, that’s not what it’s here to do. We’re trying to draw the connections between the incentive structures of massive spending and those who aim to gain from it. And one thing is for certain — if you can’t engage in a foreign war, a crisis at home is the next best thing.

In March 2020, I was running my own small business at the time. Nobody wanted to buy anything from me, and mania had set in as COVID-19 made its way into the United States. People were being laid off en masse, necessities were flying off store shelves, some were convinced these were the end of days.

Lo and behold, they weren’t. Within a week of the virus moving through Italy it was known and understood that it generally targets those with vulnerable immune systems, namely the elderly and populations with significant comorbidities. Instead of the United States taking the approach of encouraging temporary isolation for those groups while the virus moved naturally through the rest of us, the country was put on full doomsday mode.

Everybody was treated not only like they had a high chance of dying from the virus, but also that they would kill everybody they met if they went outside. Businesses were shuttered and the economy sputtered to a halt – but people needed to get paid somehow, even if it was with magically-printed fiat money.

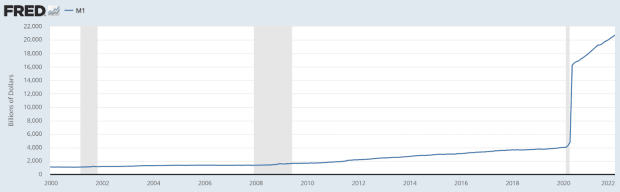

M1 Money Supply through 2022

Through February 2022, nearly $4 trillion has been spent in economic packages intended to jog the economy. We’ve propped the system up by flooding it with dollars that do not represent any real earned value. The U.S. debt-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratio is sitting at 133.46%. Every dollar of productivity is trounced by one dollar and twenty-eight cents worth of debt: Does that sound like a healthy economy?

The Federal Reserve Board launched the Municipal Liquidity Facility in April 2020, which was just a mechanism to purchase $500 billion of short-term notes from all 50 states and some of the most productive cities in the country. They also relaunched multiple great recession-era programs to buy assets from United States companies with newly-manifested counterfeit money, adding trillions more to the balance sheet of the government.

Despite having more open roles in the workforce than ever before (comparative to unemployment), some families are going to be receiving as much as $14,000 from President Biden’s newest COVID-19 relief bill. Make it make sense.

Under the guise of giving money to the people, the Fed (unintentionally or not) has diluted wealth from the people by way of leveraging the COVID-19 pandemic. Everything from asset purchases, to buying notes from the treasury, even literal helicopter money into the hands of every American, three separate times.

The Cantillionaires reap the benefit of accessibility to freshly-minted dollars, while the factory workers and schoolteachers had their grocery prices increase, and their lives put on hold. Because of this irresponsible expansion of the money supply, people are working even harder to earn a currency growing ever weaker, while the cost of most goods and services people wish to purchase rises.

Under a bitcoin standard, an economic shutdown and the minting of trillions of dollars simply is not possible. With something like bitcoin, you cannot mint new units of the currency at will – value that gets transacted always represents underlying earned value, through labor or the sale of goods and services. Since you cannot mint new units in times of crisis, a bitcoin standard would have forced the United States Congress to think more critically of how best to respond to the pandemic.

We discussed earlier about those who are at great risk from the virus. Under a bitcoin standard, the U.S. would’ve had to take a fiscally responsible approach; no longer having access to printed money would mean they’d need to think efficiently. Their efficient response, likely, would have been to encourage isolation for vulnerable populations, mobilize capital collected through taxes to areas with higher densities of these more-susceptible people, and nothing more.

Under a bitcoin standard, the government is forced to think efficiently. No helicopter money, no emotionally-charged asset purchases with the fear of total economic collapse, and no shuttering the complex web of relationships that is the U.S. economy. Strategy and prudence naturally froth to the top of the pot using a sound money standard; especially over the fiat response of extravagant spending packages and hastily drawn together decision-making.

A bitcoin standard would disable the government’s ability to inefficiently allocate free, unearned capital in times of crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic should be a shining example of their inability to do so. The free market should allocate capital as it sees fit, maximizing efficiency and prosperity for all. Bitcoin gets out of the way where fiat creates a blockade.

The Next War

At the time of writing, the United States is threatening to take offensive action on Russia following their invasion of Ukraine. Meanwhile, we utter a collective sigh of “here we go again.” But remember why this article is being written, to explain the incentive structures involved in going to war, and why the United States is chomping at the bit to do so.

New war means new printing, and the United States is on high alert to gaslight the American public into why this war is an outright necessity. In 2014 The Washington Post published an op-ed opinion piece titled “In The Long Run, Wars Make Us Safer And Richer,” which I believe is filled with uncorrelated statistics to bolster the false claim that war increases long-term domestic productivity for the United States. We should perhaps get ready for more justification, rationalization and outright lies as to why raising the debt ceiling is a national emergency, and printing another $10 trillion will make life better for everybody. They’ll need to lie through their teeth to get away with any more of this, as they always have.

Bitcoin fixes this. The only means of funding a war without fiat and/or more taxes (which must be approved by those running for future office) are explicit and voluntary – either through issuing domestic debt (war bonds) or foreign debt, made even more voluntary with bitcoin, given that seizure is difficult.

Bitcoin defangs the wretched and sharp fiat teeth out of the government’s maw. Trigger-happy politicians who salivate at the thought of trillion-dollar war spending packages will have their temperament tested; they’ll be made more prudent and strategic by way of bitcoin’s programmatic scarcity. You can’t fight it, but you can use it.

Final Thoughts

Endless conflict and strife, whether at home or abroad, is enabled by the ability to create money by decree. Since the United States needs to pay down their debt and is incentivized to retain control over the money, they are never going to switch to a hard money standard with bitcoin.

That’s fine, if you cannot convince the country to adopt bitcoin as their monetary standard, buy and hold it yourself. Whenever possible, transact exclusively in bitcoin. Slowly as we create these circular economies, companies will allocate to the asset, goods will start being denominated in bitcoin, and life on a bitcoin standard becomes more and more inevitable.

Feedback Patterns in the Bitcoin Economy – Image source

Speculatively attack the dollar on an individual level; don’t allow them to tax you even more than they already do. Legally deprive them of spending power, as they can’t inflate away your wealth as much if you minimize your exposure to the dollar. Make it known through your actions that you do not wish to engage in another decades-long war. Have you had enough of them? I know I have. I’d like to know what it’s like to go at least half of a decade without getting frisky for another foreign conflict. Let’s make it happen.

You can find me on Twitter @JoeConsorti, thanks for reading.

This is a guest post by Joe Consorti. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.