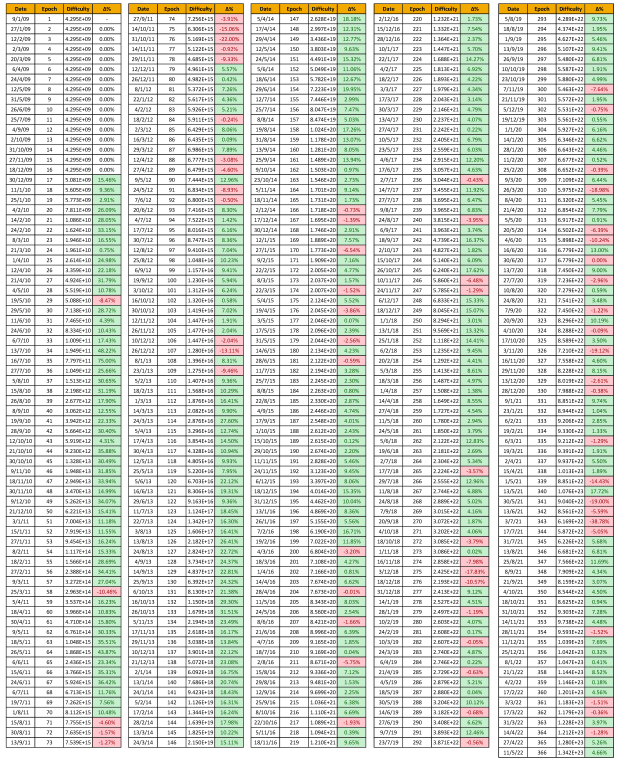

As of the date of this writing, block 737,000, Bitcoin is almost two-thirds into its 366th difficulty epoch. A difficulty epoch is a period in which 2,016 blocks are added to Bitcoin’s ledger, ideally in 20,160 minutes, or 14 days. If the epoch ends in less time, the network adjusts the difficulty of successfully mining a Bitcoin block upwards to regain a 10-minute block cadence, and vice versa. The entire history of Bitcoin’s difficulty is shown in the graphic below (you may need to zoom in — it’s quite a huge graphic).Figure one: Historical Difficulty Changes Since Inception

Figure one: Historical Difficulty Changes Since Inception

In total, 15 epochs, around 4% of all epochs, experienced no difficulty change. These just so happened to be the very first 15 epochs where basically just Satoshi Nakamoto, Hal Finney and a few dozen other people were mining. Of the remaining 351 epochs, 283 (77.5% of all epochs) would see a difficulty increase, with 67 epochs seeing a difficulty decrease. We will delve into these periods of decrease later in this piece.

Toward the end of 2009, Nakamoto made a plea to the greedy, opportunistic Bitcoiner community to not mine with their GPUs. And I quote, “We should have a gentleman’s agreement to postpone the GPU arms race as long as we can for the good of the network. It’s much easer [sic] to get new users up to speed if they don’t have to worry about GPU drivers and compatibility. It’s nice how anyone with just a CPU can compete fairly equally right now.”

Bitcoiners being the greedy opportunists that they are (this, by the way, is great for Bitcoin, as it drives all innovation) broke this gentleman’s agreement, and the GPU mining era would commence, and eventually, so too the ASIC mining era, but more on that later.

Figure two: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2009. Here we see that Bitcoin doesn’t even have a market price, and difficulty is stable for the entire year, save for one large jump at the commencement of the GPU mining era at year’s end.

In 2009, the average difficulty increase was 0.966%, with a standard deviation of 3.865%. Obviously, since bitcoin didn’t have a market price in 2009, profitability calculations are moot, but if you didn’t add any CPU or GPU power, for the year, if you were earning 1 BTC at the start of the year, you would earn 14.39% less, or around 0.8561 BTC, by the end. Obviously, this assumes the miner has 100% absolute uptime, and doesn’t lose income thusly (highly unlikely, but let’s be generous!).

2010 To 2013: The GPU Mining Era

Summary Difficulty Statistics: 2010 to 2013

2010

In 2010, we witnessed bitcoin acquire a market price for the first time in its history, as well as its first exponential “price rip” upwards. Aside from one difficulty drop in May (before Bitcoin had a market price), we saw 32 difficulty increases with an average of 22.85%, and a standard deviation of 15.54%. If you were earning 1 BTC per hashing unit on January 1 of that year, and didn’t spend any more money on additional GPUs, by December 31 you were earning 99.98% less, or about 19,178 sats instead of a whole coin. Rough.

Figure three: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2010

2011

2011 wasn’t much better for the miners than 2010, where if you were earning 1 BTC per hashing unit at the start of the year without adding to your GPU fleet, you would be earning 97.81% less, or about 2.19 million sats — technically over 100 times better off than you were in 2010, at least!

2011 saw bitcoin’s first mega-pump, with price increasing about 100 times from $0.30 to $30 in the first six months of the year, before taking a 93.3% bath back down to $2 by November. One difficulty drop was experienced during the 50% price drop between February and April, with the other eight drops for the year occurring during “bath time.” There were 21 increases throughout the year. The average difficulty adjustment was 11.96%, with a standard deviation of 16.96%.

Figure four: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2011

2012

2012 was an interesting year, as it was the first time that the industry would ever experience going through a block reward halving. While you could fetch around $7 for a bitcoin in early January, a Valentine’s Day massacre nearly halved the price, and price was consistently down 30% to 35% from the January high until the middle of the year. This resulted in five difficulty drops in that six-month period. A doubling in price from June to August saw healthy difficulty increases again, with no drops in difficulty to be witnessed until “The Halving” in late November, which saw two consecutive difficulty drops to end the year.

There were 20 increases throughout the year, and seven drops, with the average difficulty adjustment being an increase of 3.26%, with a standard deviation of plus 6.04%. You would be earning 59.11% less on December 31 if you hadn’t invested in any new hardware for the year. Not too bad compared to previous years.

Figure five: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2012

2013

Aside from a 9.46% drop in difficulty in late January, 2013 would be an “up only” year thanks to two mega-pumps, the first a near-20-timeser, going from $13.22 at the start of the year to $229.47 on April 9, and a 17-bagger from early July until early December. Alongside the solitary difficulty drop to start the year, there were 30 positive adjustments, averaging 17.16% with a standard deviation of plus 8.34%. Similar to 2010, your 1 BTC of earnings on January 1 reduced to 292,156 sats if you didn’t add any GPUs to your farm, a 99.71% drop. However, as of the end of 2013, nobody would be adding any GPUs to their farms (aside from shitcoin miners of course!), as the age of the ASIC was now upon us.

Figure six: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2013

2014 To 2020: The ASIC Mining Era

Summary Difficulty Statistics: 2014 to 2019

2014

Despite the collapse of Mt. Gox starting the longest bear market in the history of Bitcoin, with the high watermark of $1,134.39 not to be passed again for the final time until April 2017 — a full 1,218 days later (trust me, as a November 2013 first-time buyer, I lived it and was counting the days!). 2014 was yet another seemingly “up only” year for difficulty, with 28 increases, and two small decreases of 0.73% and 1.39% to round out the year. The average difficulty change was plus 10.9% with a standard deviation of plus 6.57%. If you didn’t add any ASICs to your farm in 2014, your 1 BTC of earning power was slashed by 96.86% to 3.14 million sats.

Figure seven: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2014

2015

Even with Mt. Gox being dead for almost two years, the “Goxxings” just seemed to keep coming, with price bouncing between $300 and $150 for most of the year, with all five of the difficulty drops occuring in 2015 coinciding with sharp 30% to 50% drops in price over a short time period. ASIC manufacturers were still feeling out the space and perfecting their art, as shown in the graphic below from the Cambridge University SHA256 technology tracker. This meant that the average difficulty change for 2015 was only plus 3.31% with a standard deviation of plus 4.62%. Still, if you didn’t add any rigs to your farm, your 1 BTC of earnings on January 1 was cut by almost 60% to 0.403 BTC.

Figure eight:. Source: Cambridge University SHA-256 State of Technology Tracker

Figure nine: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2015

2016

2016 was one of the most special years in mining history, as it witnessed a halving as well as the release of the AK-47 of mining rigs, the Antminer S9, which would enjoy profitable service for six years up until the very recent major price drop witnessed in May 2022.

Price growth for the year was sluggish, save for the last few months which saw substantial growth, and the goxxings would still continue during 2016 despite the exchange collapsing more than two years prior. All of this would result in 22 difficulty increases, and five drops, three of which occurred prior to the halving.

The average change was plus 3.93% with standard deviation of plus 4.93%, resulting in a reduction of BTC income of 47.36% for the year.

Figure 10: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2016

2017

2017 saw two major events, a 20-times run up in price throughout the year, and the resolution of “the blocksize war” toward the very end of the year. I obviously cannot do justice to the blocksize war in one paragraph, so I will quote the blurb of Jonathan Bier’s seminal March 2021 book “The Blocksize War: The Battle Over Who Controls Bitcoin’s Protocol Rules”:

“[The Blocksize War] was about the amount of data allowed in each Bitcoin block, however it exposed much deeper issues, such as who controls Bitcoin’s protocol rules.”

The ultimate resolution was the creation of a new fork of Bitcoin, known as Bitcoin Cash (BCH), which could also be mined using the SHA-256 protocol. Huge increases in the price of BCH toward the end of the year were enough to coax miners away from mining the Bitcoin network and mine on the BCH network on three occasions after its launch in August, with a small drop in July taking the tally to four downward adjustments for the year.

There were still 23 increases for the year however, and with an average change of plus 6.16% with standard deviation of plus 6.15%, these changes resulted in a reduction of income of 82.06% for the year. More mining rig manufacturers would enter the game this year, but no dramatic improvements in rig efficiency were achieved.

Figure 11: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2017

2018

2018 saw much more competition in the ASIC hardware space, with rig efficiency almost doubling. Rigs were becoming so efficient, having an 80% drawdown in price over the year did little to stop hash rate growth.

There was an average change of plus 3.59% with standard deviation of plus 7.31%, across 23 difficulty increases, a drop in July when bitcoin’s price was at about $6,000, and four drops which occurred during the final price capitulation from about $6,000 to about $3,000 late in the year. The end result was a reduction of income of 64.09% for the year compared to your start-of-year earnings.

Figure 12: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2018

2019

After the brutal bear market of 2018, traders saw a relief rally that took the price from $4,000 at the start of the year to about $13,000 mid-year. Aside from five minor negative difficulty adjustments of less than 1% in the first half of the year, and two drops in the second half of the year when bitcoin would return to a price of $6,000, there were 19 increases. The average change of plus 3.06% with a standard deviation of plus 4.49% resulted in a reduction of income of 55.42% for the year.

This was mainly driven by even more competition and efficiency gains in the ASIC hardware market as opposed to chasing price-cost arbitrage, with the 2019 fleet of new rigs being more than twice as efficient as their 2017 peers. 2019 was also the first year we saw modular mining techniques at large scale, where miners would essentially turn shipping containers into portable ASIC farms, and simply ship them to the world’s cheapest power sources. The large drop in difficulty in late October was more likely from Chinese miners physically migrating to cheaper hydroelectric power sources due to the wet season, than a miner capitulation over a small drop in price. This would become far more apparent in the migrations of 2020.

Figure 13: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2019

Summary Difficulty Statistics: January 1, 2020 to May 10, 2022

2020

The most difficulty drops in Bitcoin history would happen in 2020, with 11 drops, some of previously-unseen magnitudes, occurring throughout the year, for different reasons. Despite the “COVID-19 everything crash of March 2020,” the substantial hash rate drops witnessed in April and late October would mostly be the result of Chinese miners physically migrating from Xinjiang province (which is coal heavy) to Sichuan province (which is hydro heavy) during the wet season, and then back at the conclusion of the wet season. The profit on offer was so great as a result of much cheaper power that it was worth it for miners to simply pack up, move and establish themselves elsewhere, despite the associated risk and downtime. Of course, the halving of May 2020 would result in two consecutive drops of 6.39% and 10.24%.

Mining techniques and rigs would continue to improve, with firmware service providers like Braiins.OS providing miners with software that dramatically increased the efficiency of their rigs and was easy enough to use by mining enthusiasts. Immersion-cooled mining would also start being used by various operations as a way to further increase efficiency and reduce downtime and maintenance costs.

The average change of plus 1.06% with standard deviation of plus 7.74% resulted in a reduction of bitcoin-denominated income by 24.91% for the year. Considering that the price of bitcoin would grow by four times in 2020 however, this would start a period of time where home and collocated mining started to look more appealing to a far wider user base due to the seemingly irresistible cost-price arbitrage on offer in a booming market, seemingly protected from competition, at least temporarily, due to the COVID-induced global supply chain issues afflicting the market.

Figure 14: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2020

2021 To Current: China Bans Bitcoin And The (Near) Instant Recovery

2021

2021 was the year mining “hit the streets,” with colocation companies booming despite long lead times for delivery, hardware prices were going through the roof (in near lockstep with the price). Mining companies were still migrating for the cheapest power. They were going public at a rate of knots, and corporate treasuries were collateralizing their bitcoin in interesting ways. Just some of the mania you would expect to see during a meteoric bull run. To top it all off, there was a huge blackout in China which caused a near 15% negative difficulty change, then, only a month later China totally banned Bitcoin mining, causing four consecutive negative difficulty changes of 19%, 5.6%, 38.8% and 5%. This meant that anyone who was already mining saw a huge temporary bump in profits, and would be forgiven for thinking, “Whoever isn’t considering getting into mining right now would be stupid!”

But if you’ve stayed with me up until this point, you know how this story ends. Good times are short, and are always followed by cripplingly hard times for miners. These times would come soon. Those saying the Chinese hash rate would not return for months or years were selling the most picks and shovels, but return it did, mostly within three months, and all of it by the end of the year.

There were 19 increases, and seven drops — five of which were related to China, the other two small and within tolerance. The interesting statistic to look at is the standard deviation, and while difficulty averaged a change of plus 0.5%, its standard deviation was 10.9%. So, if you were in the game at the start of the year, you performed stellarly, and only had your income reduced by 12.33% for the year. However, if you were one of the unlucky ones who started in late July 2021 (or later), you had 12 changes for the rest of the year (11 of which were positive), and an average of plus 4.61%, meaning you’d lost about 77% of your income by the end of the year, with the bitcoin price going south, quickly. Again, if you were already established, 2021 was a fantastic year. For everyone else, buying bitcoin would have been the wiser option.

Figure 15: Difficulty vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2021

2022

We are 10 difficulty changes into 2022 — seven increases and three drops. Despite a 20% crash in price since the last difficulty change, it is predicted that the upcoming difficulty change will be a drop of around 1%. Of the ten changes so far, the average change was plus 2.44% with a standard deviation of plus 3.39%, resulting in a reduction of income of 21.89% year to date, but I predict it will be a reduction of 50% by year end. Home miners beware!

Most interestingly, 2022 saw Intel enter the mining game, forming a large partnership with green miner GRIID, and word that even oil-and-gas giants Exxon Mobil and Conoco Philips had started flare mining using mobile, containerized mining solutions. Even with bitcoin’s price being in the doldrums, competition has been getting stiffer and stiffer.

2022 has seen more COVID-19 supply chain issues clearing, more innovation in mining firmware and techniques and, with what looks to be yet another protracted bear market for price, will see a flushing out of over-leveraged or low-margin miners, as we have witnessed in previous bear markets.

Figure 16: Difficulty Vs. Price, Log-Log Scale, 2022 to Date

Conclusion: Bitcoin Mining Is Perfectly Competitive

The nature of competition in Bitcoin mining is near perfect which means miners will work extremely hard to have the most efficient operation, and indeed, the most efficient supply chain. It also means that they are ready and able to physically go wherever is required to achieve this. Mining is not easy, and for a home miner, is akin to panning for gold in 2022 — it sounds far more glamorous and rewarding than it actually is! There are better ways to pique your curiosity about mining than spending money trying it out yourself (read: going short spot-Bitcoin in hopes you’ll earn more by mining versus going long spot-BTC) — but you will never hear this from the people selling picks and shovels!

Bitcoin mining has been able to absorb most of my time and intellectual capacity for eight years, yet I have never even turned on a miner in my life. When it comes to mining, it’s best to leave the bread to the baker, as they are most capable of identifying, assuming and managing the risks. The history speaks for itself: When it comes to hash rate and difficulty, “number go up” harder, faster and more consistently than price, and while this is great for Bitcoin, it is terrible for those looking to compete in what is a perfectly competitive space.

This is a guest post by Hass McCook. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.